Native container gardens are much easier to set up than full-size gardens. If you’re new to gardening or have limited space, native pots are a gateway to sustainable gardening on a larger scale. Placed alone or in groups, the containers are versatile little packages that can be moved at will and are easy to care for. The color palette of natives is more subdued, like nature, and you will find that you will appreciate the foliage of many of these plants more than the flowers.

Gardeners and design professionals around the world are embracing wildlife gardening and landscape design that mimics nature, and you can do it on a limited budget and with little time spent creating a container. A word of caution: never extract wild plants from the forest. Grow them from seed or purchase plants from a reputable nursery.

Beauty made easy

My first requirement for a beautiful native container is a large, expansive container (at least 15 to 17 inches deep and 19 to 20 inches wide). Large, because you want your plants to have good soil functioning and require less frequent watering. Less crowded plants will also show up better. Start simple with one to three plants and use one tall plant, one plant that fills the pot, and then some filler that spills over the edge. With this simple recipe, you can have an attractive, pollinator-friendly container in no time.

Tips to get started

Make sure your container has large drainage holes, as drainage holes often become clogged with roots over time. This happens when you have plants in containers for several years. I often make additional drainage holes in the container (if it is recycled plastic) or make existing ones larger. If necessary, you can use a threaded rod and pierce the root mass from the bottom up. I only do this when I don’t want to disturb existing plants, but I can see that it doesn’t drain properly.

Once your container is established, keep dead foliage clear, but I leave the flowers to produce seeds for birds, so don’t cut them off (remove spent flowers).

I usually include some type of grass in a native container, as the silhouette of grasses is very different from other perennials and gives the pot some textural interest. Mostly low-maintenance, grasses are often overlooked as an excellent native plant option. There are many native grasses to choose from: Blue-Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium), Soft Rush (Juncus effusus), and Carex Pensylvanica (Pennsylvania Sedge), are just a few examples to try.

Also think about the colors of your foliage as they appear at the end of the season. Narrow-leaved blue star (Amsonia hubrichtii) is a great example of producing wonderful blue star-shaped flowers in the spring that attract butterflies (mostly swallowtails) and the foliage turns bright gold in autumn, which is almost more striking than the flowers. Therefore, it is important to think about whether a plant has multi-season interest.

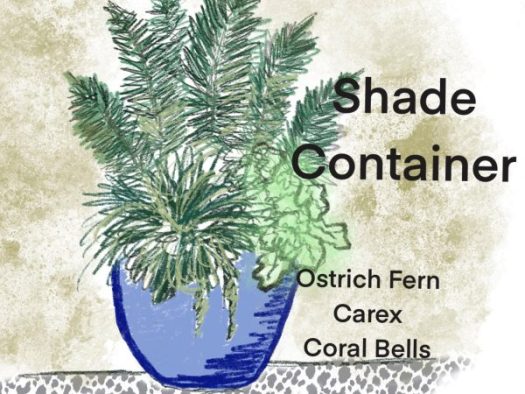

shadow container

Shady situations will require greater use of colorful foliage plants, especially ferns and grasses. These plants can remain in a container for at least 5 years until they need to be dug and divided. Fertilization is important after the first year, when many nutrients will be depleted by growing for a full season. I use a solution of water and liquid fertilizer mixed in a watering can for easy application and water it to give the plants the necessary nutrients. Be sure to use a winter-proof container so your plants can overwinter without breaking the pot. Some plants have become so rooted that some of my pots have split. That’s the time to dig in and divide safely!

For my shade container, I used ostrich fern (Matteucia struthiopteris), subsensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) as the focal plant. The herb is Carex pensylvanica), sub Soft Rush (Juncus effusus), and top it off with Coral Bells (Heuchera Americana), sub Wild ginger (Asarum canadensis). This combination will accompany you for many years and will remain beautiful for most of the year.

Solar containers

Containers exposed to the sun will definitely require more frequent watering than a shaded container. Plants will also grow faster and need more fertilizer, so watch for wilting plants for a signal to water thoroughly. When plants are a couple of years old and become root-bound, watering tends to run down the sides of the root ball, rather than soaking in. That is the time to divide and divide ourselves.

For my sunny container, the focal plant is Aster laveis ‘Bluebird’, sub Beardtongue ‘Husker Red’ (Penstemon digitalis), Threadleaf Coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata) and Wild Pink (Silene caroliniana) sub Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa). This combination will bloom at different times during the growing season to give you something that will bloom all spring and summer, extending the period of interest for pollinators.