As stewards of our amazing planet, we can appreciate the potential importance of all species to the continued existence of a complex ecosystem. But there are some that stand out and do the heavy lifting. Specific integral species are more important than others for the sustainability of an ecosystem and are called ‘Keystone species’ – organisms that support the entire ecosystem and stabilize complex and highly connected food webs.

According to Douglas Tallamy, famous ecologist and entomologist, just 5% of our native plant genera support approximately 75% of our caterpillar species, which support our native bird populations. For example, a titmouse must catch between 6,240 and 9,120 caterpillars to raise a clutch of babies, according to him. And surprisingly, caterpillars transfer more energy from plants to other animals than any other insect.

Similarly, in the plant kingdom, there are key plants that play a huge role in the sustenance of other species. In the Mid-Atlantic region, native oaks (Quercus), willows (Salix), birches (Betula), black cherry trees (Prunus), pines (Pinus), and poplars (Populus) top the list supporting the greater number of lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), which in turn feed birds and other wild animals. And in the case of herbaceous plants, goldenrods (Solidago), asters (Aster), perennial sunflowers (Helianthus), bee balm (Monarda) and Joe Pye grass (Eupatorium), are important for the food web by supporting many different types of insects. As a homeowner and gardener, these are a great starting point for transforming your backyard into a conservation oasis that provides habitat for wildlife.

I live in the mid-Atlantic state of Maryland, and the natives I plant would be different from other parts of the country, like California. A red oak planted in my area would harbor many more insects than if it were planted in a non-native area, such as the Pacific Northwest. So before planting, research local natives that are indigenous to your area.

Smart plant choice will support the insects that maintain plant diversity and support the insects that contribute the most energy to the food web. Intentional plant choice should be based on plants that are native to your particular ecoregion. Verify The National Wildlife Federation website, determine your ecoregion and plant the things that will benefit the most species.

According to Douglas Tallamy, author of Bringing nature homeOak trees (Quercus) are the number one tree in the United States supporting the greatest insect biodiversity, with up to 557 species of lepidoptera. There are a variety of native oaks from different parts of the country that you can choose from. A useful reference is Field Guide to Native Oaks in Eastern North America. Oaks are also called “mast trees” which is simply a tree that forms acorns or other nuts and these further support wildlife as essential food.

Working as a landscaper, when a client wants to plant a tree, they typically focus on a showy, spring-flowering tree, such as the Japanese weeping cherry (Prunus sp.) or Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana), which support a fraction of insect species. . What does an oak tree do? But an oak tree is difficult to sell because of its insignificant flowers and the belief that it grows slowly.

And in the case of the Bradford pear, it has invaded wild areas and taken over them to the detriment of native species. Instead, I always suggest, for longevity and wildlife importance, one of the native oaks, such as white oak (Quercus alba), willow oak (Quercus phellos), red oak (Quercus rubra), or oak pin (Quercus palustris). The prolonged fall colors are an advantage for these trees, long after the maples have lost their colorful leaves.

Another beautiful large tree that is important for insects are maples (Acer), which support 285 species of lepidoptera (butterflies). The sugar maple (Acer saccharum), one of my favorites, has a deep fall color of red, yellow and burnt orange and is the iconic tree used to collect sap for maple syrup. Needing a lot of space, sugar maples brighten the autumn landscape. Another good option are the birch trees (Betula), which are home to 413 species of lepidoptera, and the river birch (Betula nigra), which I grow, has wonderful exfoliating bark for all seasons.

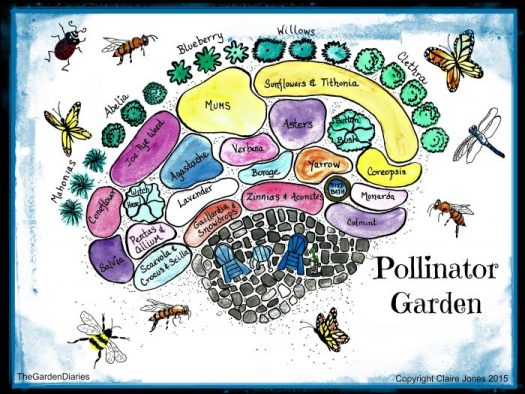

Many of us have only a small property or perhaps just a few containers in a yard. Perennials are the solution to providing the greatest benefit to wildlife and providing key attributes in a smaller space. Small shrubs will also work, such as blueberries (Vaccinium) or chokeberries (Aronia). Plantings of Black Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia), Aster (Aster), Phlox (Phlox), Milkweed (Asclepias) and Bee Balm (Monarda) would create a long flowering potted oasis that can attract and nourish a host of insects. Many people only plant annuals, ignoring perennial options, in their containers, but perennials will return each year with little care in pots. They don’t bloom as much as annuals, choose perennials with different flowering times to have something that blooms all season long. Anise Hyssop (Agastache) blooms for weeks in a container and I watch a constant parade of butterflies and other natives visit the flowers for weeks in mid to late summer from my patio.

Diversity is the key here. Include a wide variety of plants to attract beneficial insects and pollinators to your garden, preferably planted in blocks or groups. A mass of the same species approximately 3′ by 3′ provides a target for pollinators to target. Food, shelter and water are important for creating a welcoming, healthy ecosystem in your garden and keystone species give you maximum performance.

Should you continue planting and enjoying non-native plants? Yeah!! Non-native species, such as butterfly bushes, still provide nectar and pollen to pollinators, but do not act as a host plant for caterpillars. There are sterile species of these that do not set seeds and can play a valuable role in the garden. This is a controversial position, but I think if you plant at least 70-75% native species, you can add some fun non-natives to generate interest and even more diversity. There are many non-native species that provide valuable food for wildlife, but make sure they are not on the invasive list. Check out this article – Natives vs. Non-natives and invaders for a good explanation of this. Don’t pull out all your non-native plants! Gradually add new native plants to your garden as plants die back and reinforce your key native choices.

I am in the process of converting a completely non-native landscape into a mostly native landscape for a client. What was once filled with liriope, pachysandra and shrubs such as azaleas and nandinas is gradually transforming into native plantings. We uprooted some defective rhododendrons and nandinas and replaced them with serviceberries, eastern red cedar, aronias, clethra, winterberry, and the native ground cover of Pachysandra (Pachysandra procumbens). It has been a gradual process and now my client has 70% native species, instead of 100% non-native species. It can be done, but address each area separately to stay within your budget.

Homeowners associations also need to be informed and treated. Sometimes they are not receptive to change in the form of native plants that are not as familiar to them. But education is key here. Let your neighbors know what you are planting and, more importantly, “why,” so you can involve them in what you are trying to accomplish.